|

| Adolf Hitler's Arrival at Balmoral Oil on canvas 107cms x 137cms 2024 |

My mother and father were married in September 1939, the day before Britain declared war on Nazi Germany. This was not an auspicious moment.

|

| Adolf Hitler's Arrival at Balmoral Oil on canvas 107cms x 137cms 2024 |

|

| The Muckle Coastguard Oil on canvas, 760mm x 1202mm |

|

| Creish hills from Kingshouse Inn Mixed media on paper, 38 x 56cms. |

|

| A Marxist Aesthetician Oil on canvas. 66 x 41cms. |

|

| 1743. The last wolf in Scotland Oil on canvas, 66cms x 86cms |

Deep in the hills grew a forest. In this forest was an open, heathery glade. In the middle of this glade was a great heap of boulders, believed to have been thrown there by giants of a previous age.

At the edge of this clearing, hidden in the heather, lay a man and a boy who were spying on the boulders.

"Now is the time," said the man, "The adult wolves have gone, lets get the cubs."

The entrance to the den was a narrow tunnel under the boulders.

"I am too broad to get in there," said his father. "Take this club and go in and smack the cubs on the head."

The boy was keen and without hesitation squirmed up the tunnel. The man leaned on his knee and peered into the darkness, completely unaware that the mother wolf was bounding up behind him. She brushed past him angry and snarling and started frantically wriggling up the tunnel to save her cubs.

"Father! Father! Why has it grown so dark?" cried the boy.

The man did the only thing he could and grabbed the wolves tail. He braced his feet against the banking and pulled and pulled. His eyes bulged and he broke out in cold sweat. Slowly the rear of the wolf emerged. With one hand still holding the tail he grabbed his dirk and stabbed it, one, two, three times right up to the hilt.

"Are you all right son? I thought you were about to become the wolves dinner."

The boy pulled out the bodies of the wolf cubs. The father cut off their tails and that of the mother.

"Well" he said," Not a bad days work. The chief will pay a fine bounty for our trouble."

Later that day the rest of the pack returned to the scene of the slaughter. They were muzzling round the bodies when they heard a whining coming from the den. A young female entered and gently carried out a surviving cub in her mouth. Although she had no milk she regurgitated some partially digested meat so that the little wolf could eat.

The man did not receive his hard earned reward personally from the Chief, as he had hoped, but the estate factor. The present Chief was often away from home, on affairs of State, it was said, but in reality living in London gambling and whoring. He had lost heavily at the gaming tables and was short of money. Returning north he looked around the land of his people to see what could easily be converted into gold. Now, at this time there was great talk about war with France and the navy needed timber for ships and wood to fuel the furnaces that smelted the iron to make cannon. The chiefs eyes settled on what remained of the great forests. So the wolf grew up in a world that was shrinking, as the great trees of the forest crashed down.

2. THE TINCHEL

The chief had some of his southern friends staying with him in the castle. One night, at dinner, an English Lord expounded at length on the glories of English hunting and the superior quality and quantity of game on his estates. The chief grew red and puffed out his chest.

"Hunting, you say! Hunting! I will show you hunting."

Next morning he called in his factor.

"Who is our best hunter?"

"Macqueen,"

"Bring him to me," ordered the chief."

"I would have a tinchel" said the chief, "can you organise that?"

"Yes, it is possible. But the old dyke is fallen down in places and needs repair."

"Take who you need. You can have all the men. Bring out the whole glen if need be. I aim to give my lowland friends a hunt to remember."

In the half light of dawn hundreds of men assembled on the green in front of the castle so that Macqueen could give them his orders. These were simple but not so easy to do. They were to march up the glen onto the high moors, then spread out in a great semicircle. The next morning they shook the dew from their plaids and started beating the heather with sticks and shouting. They chased everything before them; mountain hares, foxes, wild cats, roe deer and great herds of stags and hinds.

At the narrowest point of the glen Macqueen was overseeing the rebuilding of the high wall. This ran from hilltop to hilltop across the glen with only a narrow gap on the valley floor. Through this gap the wild things would be driven. The chief came riding up with his friends and gillies were busy loading muskets. Stacks of arms, dirks, broadswords and old Lochaber axes were being distributed to whoever was strong enough to use them.

When he had done all he could he climbed up the slope out of the way of stray shot and crouched on a boulder. From his perch he could see deer streaming down the sides of the glen as the ring of men tightened. Then it appeared to him as if the valley floor was moving. They were surging through the open woodland like an irresistible wave. When the leaders were within a hundred yards of the wall they stopped, sensing a trap. Some of them streamed up the hillside but were blocked by the high dyke. But the ring of men tightened, pushing them on. A few made a dash for the gap but as they passed through the chief opened fire and downed one. His ghillie passed him another gun, then another. Then his guests fired. The crackle of muskets was continuous now as the deer plunged and died. For a time the slaughter was obscured from Macqueen by the thick pall of musket smoke. Then the firing slowed and stopped, as they ran out of powder and ball.

With a great shout the gillies charged in, hacking and thrusting at the terrified deer. Some were cleanly killed but others ran off with blood streaming from terrible wounds. He saw an English duchess, her face blackened with gunpowder from firing a dozen muskets. She was so enthused by the slaughter that she kilted up her skirts and grabbing a dirk from a ghillie, dived into the slaughter. His hounds strained at the leash but he would not release them, for he saw an enraged stag flick a dog high in the sky with the points of it's antlers and now it hung helpless over the branch of a tree with a broken back.

When the frenzied butchery had stopped and the surviving animals fled he descended to the killing ground and set the gillies to gralloch the deer. The chieftain ordered fires to be made and brandy, claret, ale and whisky brought from the deep cellars of the castle. Women and children arrived carrying cheeses, cream and oatmeal to make bannocks with. Deer were roasted over the fires and pipers and fiddlers played for the dance.

Macqueen and the factor were employed in sorting out and classifying the game, which the factor recorded in a big book. When the chief read out the tally of slaughter to his guests his chest swelled with pride and delight.

5 roe deer.

7 roe buck.

125 red deer hinds

141 ditto stags

7 wild cats

9 foxes

3 goats

5 wolves

3. CRY WOLF

March came in and the land was held in the grip of hard frosts. The wolf was starving and driven to desperate measures. One evening she crept down to a clachan and spotted a scrawny cockerel strutting about a midden .She made a lunge for it just as a child came round the corner of the house and with the squawking bird in her mouth ran off across the infields. The child bawled on his mother who came running out and saw the wolf jump the head dyke and into the pasture. The woman told her husband who told his sister. His sister told her neighbor who was leaning on a dyke talking to a packman who was selling threads and needles. The packman called at every clachan in the glen to sell his wears so the story spread like wildfire. Before long, it was not that a child had seen a wolf run off with a cockerel but that a wolf had run off with a child. By the time the story had reached the chief in his castle a huge, black monster of a wolf had brutally dragged off and eaten two children.

"I will have it's head!" swore the chief. "Bring me Macqueen."

"Two children she has eaten." said the chief, "I will not have it."

"Ach, I passed by there today and the children are as cheeky as ever. I am thinking this story has grown in the telling."

"I mean to have it" roared the chief. "I am calling out all the men. You are the best hunter. You must come with us."

"Then let it be so" replied Macqueen, "I will see you tomorrow."

Macqueen did not wait for the morning but set out in the middle of the night. He took a track that led to the hills. The man and his dogs padded quietly along, leaving clouds of breath in the cold night air. Soon they were out of the trees and among the rocks and heather, where the moon glistened on big snow fields. They followed the course of a burn whose boulders were covered by treacherous ice, then entered a shallow gulley. A few tenacious rowan trees were growing among boulders and broken crags enclosed it on either side. At the entrance to the gulley lay a snowfield. He could see lines of frozen pawmarks leading across it and the dogs were sniffing with obvious interest. He chose a spot with the breeze in his face and a good view above the entrance to the gulley and wrapped himself in his plaid and waited.

The first grey streak lightened in the east. Ground mist covered the floor of the glen and in the stillness of dawn he heard a dog bark in a distant clachan. The sun came blazing over the eastern hills but there was no sign of the wolf. His limbs were stiff so he stretched them a little and the welcome warmth of the sun made him want to sleep. Then the dogs growled and their ears pricked forward. A dark shape was making it's way slowly across the snow field. The wolf was still too far away for an accurate shot so he waited, then thought,

"I'll set the dogs on her."

He unleashed the two hounds who spread out to cut off both her advance and retreat. In her prime the wolf would have picked up their scent sooner but Bran, the youngest, was on her before she knew it. He had more enthusiasm than skill so she side stepped and bit him so hard on the muzzle that Macqueen heard bones crack. Breaking free, she made a quick tear at his throat then bounded away. The other dog was close on her tail and over taking, bit her flank. She turned and there was a savage flurry of snarling, ripping teeth. She broke away with the other dog, bloodied and more respectful now, chasing behind her. She was within musket range but the wolf was moving fast so that it was a difficult, tracking shot. He had one chance. Macqueen fired.

"Dam it! Missed"

The wolf bounded on then suddenly it's front legs seemed to crumple and it pitched head over heels and lay twitching on the snow.

It was mid day before he returned to the glen. When he came close to the castle he could see hundreds of men and boys lazing in the park and the chief, obviously in a temper, pacing up and down.

"What time of day is this?" roared the chief, "It's too late now to go hunting."

"What's your hurry?" asked Macqueen, and threw the wolfs head down at the chieftains feet.

4. EXILES

That may have been the end for the last wolf in Scotland, or maybe not. There are other stories and other last wolves. However, this is not quite the end of our story.

After swithering this way and that the chief backed the loosing side in a dynastic dispute. He had little enthusiasm for his severed head being displayed on an iron spike in London town, so took a fair wind to France. As Macqueen was one of the few good men to survive the disastrous military campaign he employed him as body guard. The job did not last long, for in France the old chief took seriously to the brandy and died within a year. Macqueen did the only thing he knew and joined a regiment of exiles serving the French King. His martial talents were noted and he rose quickly though the ranks. He married a French girl and the family prospered, one of their sons becoming a marshal in Napoleon's army.

| Portrait of the young artist as a Tweed Prick Oil on canvas, 600 x 800 mm. 2022 I am not, never have been or ever will be a dedicated follower of fashion. The song by the Kinks said it all. That said, I have to admit I can still remember what I was wearing on the day I started at Dundee College of Art. This was because I was still a chrysalis, dressed mostly by my mum. I was wearing a striped shirt, narrow woolen tie, cardigan, sports jacket and fawn cavalry twill trousers. On my feet I wore suede Hush Puppy shoes. Under clothes consisted of string vest and pants. This was my choice as it was the type worn in 1953 on Mount Everest and I felt they had special, possibly mystical powers. This was perfectly normal in 1965 but art students weren't meant to be normal. Looking round the college canteen my gaze fell on a corner occupied by a group of final year students. This was the age of minimalist skirts and coloured tights. The girls looked wonderfully long legged, elegant and for me, unapproachably mature. The guys dressed in paint spattered jeans and wooly jumpers, with the occasional ex-army leather jerkin. They were silent and contemplative, drawing deeply on cigarettes or stroking luxuriant beards which I could never hope to grow. These, I thought, were real artists. Everything that could be said had been said. It was obvious that they were thinking deep thoughts. On that first day I felt I was dressed like an office worker and as a new boy stood out like a sore thumb. Instead of transforming into a colourful butterfly, which was the way male fashion was going at the time, it was necessary to metamorphose into a drab moth. Jeans were essential and wooly, polo neck jumpers, easily obtainable from workwear and army surplus shops. Of course, I kept wearing the string vest. On top of this ensemble, I threw an old U.S. Marines parka of Korean war vintage. It only took a few weeks to transform from a raw schoolboy to a seemingly confident art student. All the jeans needed was a suitable application of randomly spattered daubs of paint. I was happy like this for a year or so, but at the start of the new autumn term my sartorial complacency was given a rude shock. Into the studio strode my friend, John Kirkwood. He was resplendent in several yards of brown, tweed suite. He had been working over the holidays and invested in some clothes. "Wow! The suite looks fantastic. Where did you get it?" "It was in the sale at Jaegers on Princess Street. It wasn't too expensive." I have to admit I coveted this suite. However, as it would be nearly a year before I could earn any money again, I had to practice delayed gratification, a form of virtuous behavior now out of fashion. Oil on board, 458mm x 610mm. 2022 |

|

| Burntisland from Dodhead Ink on paper Private collection |

|

| The Old Ferry Pier, Pettycur Oil on canvas, 50cms x 70cms |

|

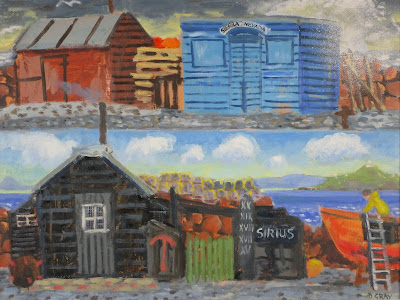

| Fishermen's Huts, Pettycur Oil on board, 46cms x 61cms |

|

| The old slipways, Abden Ink and watercolour on paper |